Today marks 52 years since the release of Led Zeppelin's fifth studio album - a record that had big shoes to fill, following the band's most highly praised work, ‘Led Zeppelin IV’.

How could they possibly match their 1971 triumph? Their answer: 'Houses of the Holy'.

With this album, the group leaned further into their experimental and creative side. Steering away from their earlier blues-heavy sound. They tried something completely different, using influences of Reggae on 'D'yer Mak'er', progressive rock on 'No Quarter', and funk on 'The Crunge'.

"There was a lot of imagination on that record... I prefer it much more than the fourth album. I think it's much more varied, and it has a flippance which showed up again later," Robert Plant reflected in 1991.

Their broad and diverse new sound received mixed reactions at first, but is now widely recognised as being Zeppelin’s peak of innovation.

To celebrate this groundbreaking album, we've explored some of its most interesting aspects:

1. The Title track isn’t on the album

Much to the surprise of Zeppelin fans - and one of the few albums to do so - ‘Houses of the Holy’ did not feature its titular track. Instead, the song featured on the band’s 1975 album, ‘Physical Graffiti’.

The band has never commented on their reasoning for the move, but it is widely thought that the song didn’t fit the Album’s feel and flow. With only limited spots on the tracklist, it’s been speculated that ‘The Ocean’ was favoured over the title track.

2. The cover was inspired by a sci-fi novel

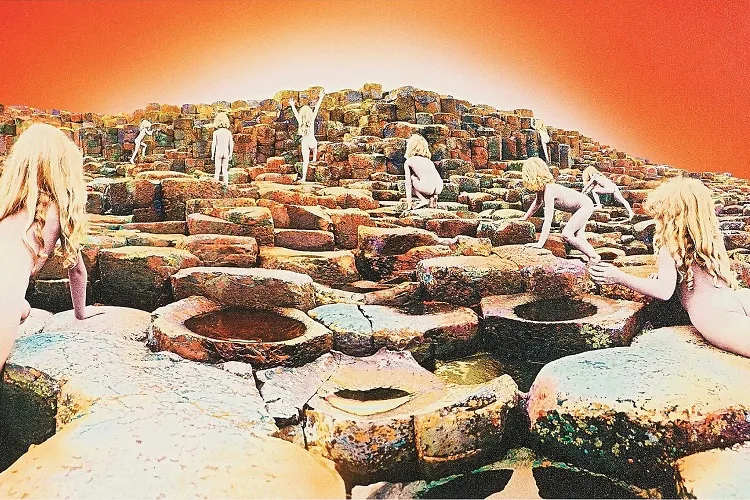

Upon picking up the album, an eerie and dystopian-looking scene awaits. The iconic cover features golden-haired children clambering up the rocks with an apocalyptic sunset on the horizon.

The art acts as a reference to Arthur C. Clarke’s ‘Childhood’s End’ (1953). A novel about humanity evolving into a new, higher existence.

Northern Ireland’s Giant’s Causeway lent the perfect backdrop for the artwork.

One of the artists behind the work, Storm Thorgerson, had this to say of the concept:

“An image of the children clamoring towards some special spot from which they might depart … It felt appropriate: civilisation climbing to a new dawn - a conception that was mythic like the band itself.”

3. ‘The Rain Song’ was a response to George Harrison

Led Zeppelin wasn’t a band associated with ballads - a point Beatles’ star George Harrison allegedly didn’t hesitate to make to John Bonham, saying: “The problem with you guys is you never do ballads.”

News of this comment eventually reached Jimmy Page, who took it on as a challenge.

The result was the track ‘The Rain Song’, which seems to include a cheeky nod to the Beatles, with its first two chords resembling the opening progression of ‘Something’, Harrison’s classic love song from ‘Abbey Road’.

4. ‘No Quarter’ was a leftover from 'Led Zeppelin IV'

'No Quarter' is one of the album’s most atmospheric and haunting tracks, although it didn't start out that way.

It was originally tested in the band’s fourth album, 'Led Zeppelin IV', at which stage it had a samba-like influence and a faster pace. It had no lyrics, but was paired with a weirdly captivating melody from Robert Plant. Also note the spectacular drumming from the one and only John Bonham.

5. ‘The Crunge’ pays homage to James Brown

With its offbeat, funk-inspired groove and improvisational style, ‘The Crunge’ served as a tribute to James Brown.

John Paul Jones’ bassline and John Bonham’s drumming emulated that of the Godfather of Soul’s band.

To further this, Robert Plant closes the track by referencing Brown’s famous live band directions, asking: “Has anybody seen the bridge? Where’s that confounded bridge?”

Brown often called out cues like “take it to the bridge” to his band during live performances.

'Houses of the Holy' marked a bold evolution in Led Zeppelin's sound and showcased their willingness to experiment. Over five decades later, the album remains a testament to the band's musical range and enduring influence.